Balloon Polyhedra

24 May 2017

Aside from the Platonic solids, there are no regular tilings of the sphere. You can’t, for instance, have a spherical polyhedron where the faces are all triangles and the vertices are all connected to 6 edges (i.e. of order 6). You need to introduce a non-triangular face, or a vertex with a different connectivity. This is why the geodesic polyhedra and Goldberg polyhedra have the structure they do: most of the faces and vertices are regular, but a small number are not.

You can, however, cheat a little. Suppose you want most of your polyhedron to be regular, but it’s OK if there’s a small region where anything goes. For example, maybe you want a regular grid over most of the Earth, but you’re only really interested in the land areas. All the irregularity can go near the South Pacific pole of inaccessibility. (Let Cthulhu deal with it, he’s pretty good at non-Euclidean geometry…)

Such polyhedra can be constructed by drawing a larger polygon over a planar grid, then contracting all the points outside the polygon or on its borders into a single point. Any duplicate edges between the same two vertices are treated as a single edge. Then, “inflate” the resulting graph into a spherical polyhedron. I call the result a balloon polyhedra, but I’m probably not the first to define this. These polyhedra can be created using the balloon.py script in my Antitile package.

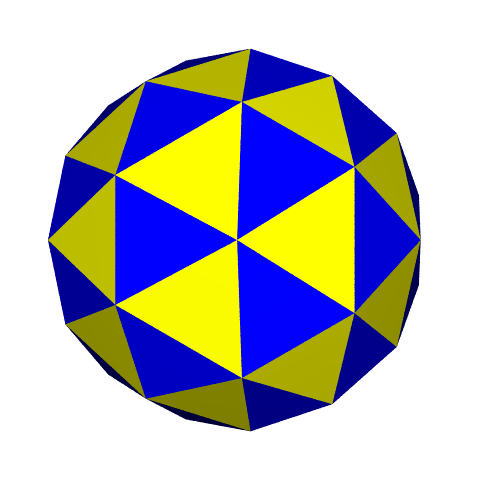

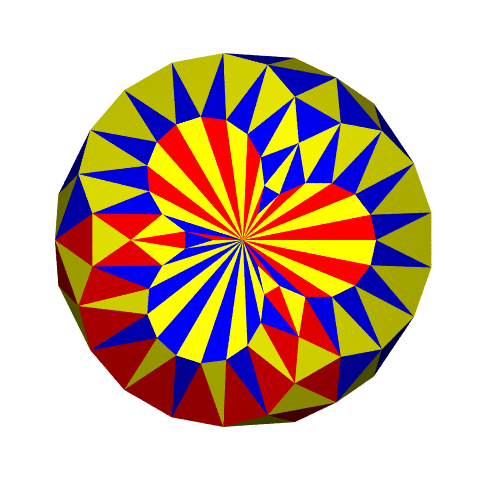

Here’s such a polyhedron, created by drawing an equilateral triangle with sides of length 15 over a regular triangular grid with edges of length 1. The coloring is a minimal coloring calculated by off_color in Antiprism. The front side looks like a nice regular grid. The back side is more complicated. Most of the vertices of the polyhedron are of order 6, but some have order 5, three have order 3, and the one at the “pole” on the back side (the point that all those other points were contracted to) has a whopping order 36.

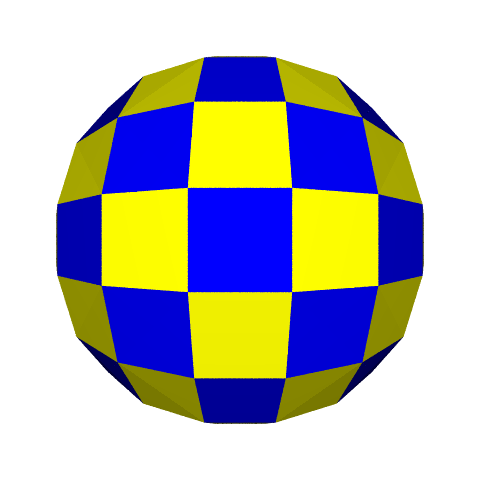

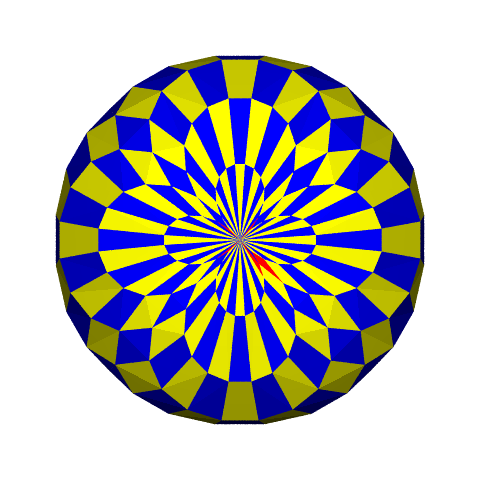

The same thing can be done with a quarilateral grid. Here’s the result of a square with sides of length 15 over a regular square grid. Most of the faces are quadrilaterals, and most of the vertices have order 4. 52 faces are triangles, though; 4 vertices have order 3, and the pole has order 52. (Note the few red faces near the pole. Also, not all the quad faces are flat; if your definition of “polyhedron” strictly requires planar faces, tough.)

With some shifting of the vertices of such polyhedron, the regular part of the polyhedron could be enlarged and the irregular part shrinked. Of course, there are significant differences in aspect ratio and size between the faces of these polyhedra. The result also resembles the stereographic projection of a triangular or square grid, but without the infinity of vertices collecting near one of the poles.

Related Posts

- 2025-08-02: 15 minutes could save you from having to understand conditional probability

- 2023-11-04: Spherical area coordinates, and a derived triangle center

- 2023-07-29: Homogeneous coordinates on the sphere with vectors

- 2022-08-30: Scaling the Schwarz triangle function

- 2022-08-27: Edges in the image of the Schwarz triangle function

- 2022-07-20: Area-preserving swirling of the disk

- 2022-03-03: Some dubious ways to calculate conformal polyhedral projections

- 2021-10-02: A variation on the Chamberlin trimetric map projection

- 2021-08-31: Snyder's equal-area projection

- 2021-06-12: Perspective projections with vectors