A (sort of) Euclidean triangle on a non-Euclidean surface

29 May 2021

A question that came up in a math chatroom (yes, I’m the kind of nerd who spends time in math chatrooms): find a “Euclidean” triangle on a non-Euclidean surface. More exactly, find a geodesic triangle on a surface with non-constant Gaussian curvature having the same sum of interior angles as an Euclidean triangle. In spherical geometry, where curvature is a positive constant, that sum is larger than 180 degrees, while in hyperbolic geometry (negative constant curvature) it is smaller. Intuitively, on a surface with regions of positive and negative curvature, maybe one can find a triangle where it balances out. (The Gauss–Bonnet theorem formalizes this notion, although here I won’t use it directly.)

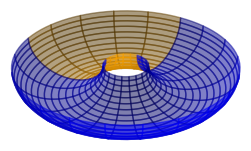

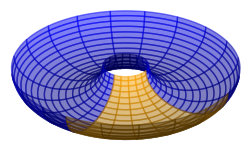

The torus is such a surface: it has positive curvature on the outer region, and negative curvature on the inner region. In general the geodesics of the torus are complicated, but there are some “trivial” geodesics: the inner and outer equators, and the meridians that cut through the torus at right angles to the equators. Let’s see what can be built out of the trivial geodesics.

Consider a geodesic quadrilateral on a ring torus (the usual kind with a hole in the middle), formed by the inner equator, a meridian, the outer equator, and another meridian. Meridians meet equators at right angles, so this quadrilateral has an interior angle of 90 degrees at each vertex. This is a polygon with the angle sum we would expect from the equivalent Euclidean polygon. It’s a rectangle! Sort of. Its edges along the meridians have the same length, but its edges along the equators have different lengths.

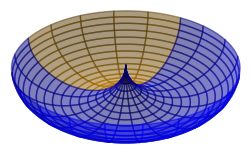

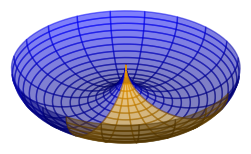

Now consider the same polygon, but on a horn torus instead of a ring torus. The inner equator shrinks into a single point at the origin, and two of the vertices of the rectangle become a single point.

Each of the meridians is tangent to each other at the origin. Thus, the interior angle at that vertex is zero. The other two vertices have right angles at their vertices, as before. Although a triangle with angles of 90, 90, and 0 degrees could not exist in Euclidean geometry, the angle sum is 180 degrees, so it meets the original criteria.

Reactions in the group chat to this “Euclidean” triangle were… let’s say, mixed.

The Jupyter Notebook used to create the images is available on Github. If downloaded and brought into a local Jupyter session, the 3d plot can be manipulated in interactive mode.

Related Posts

- 2025-08-02: 15 minutes could save you from having to understand conditional probability

- 2023-11-04: Spherical area coordinates, and a derived triangle center

- 2023-07-29: Homogeneous coordinates on the sphere with vectors

- 2022-08-30: Scaling the Schwarz triangle function

- 2022-08-27: Edges in the image of the Schwarz triangle function

- 2022-07-20: Area-preserving swirling of the disk

- 2022-03-03: Some dubious ways to calculate conformal polyhedral projections

- 2021-10-02: A variation on the Chamberlin trimetric map projection

- 2021-08-31: Snyder's equal-area projection

- 2021-06-12: Perspective projections with vectors